According to the 2020 State of Waste Report for South Africa, the country generated approximately 55.6 million tons of waste in 2017, of which just more than a third was organic. Having identified this valuable resource, the government aims to divert organic waste from landfill through composting and the recovery of energy and biogas technologies.

The article appeared in ESI Africa Issue 1-2021.

Read the full digimag or subscribe to receive a free print copy.

South Africa’s National Waste Management Strategy 2020 uses the circular economy concept as its central focus. An update of a 2011 document, the National Waste Strategy’s first goal is to prevent waste, and where waste cannot be prevented, reduce the volume of garbage. The strategy calls for reducing the total volume of trash disposed through landfills by 40% within five years, 55% within ten years, and at least 70% within 15 years through reuse, recycling, recovery and alternative waste treatment.

Amongst the strategic objectives to achieve the prevention of waste is the diversion of organic waste from landfill through composting and the recovery of energy. A further objective stipulates that there will be 40% biogas from organic waste produced by 2025 and that this strategy and regulatory framework be finalised in 2021.

Additionally, there is a planned programme linking the National Schools Nutrition Programme to biogas digester projects. As such, the intention is to equip several schools with biogas digesters. The Western Cape Government’s Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning has also set a target of 100% diversion of organic waste from landfill by 2027, with an interim target of 50% diversion by 2022.

However, it has never been easy for the biogas market to take off in South Africa. Renewable energy researcher at the University of Fort Hare, Patrick Mukumba, identified three problems, which are:

1. low efficiency of biogas compared with conventional fuels such as petrol and diesel;

2. cheap electricity cost from coal-fired thermal power stations; and

3. large amounts of hydrogen sulphides in biogas that can cause corrosion of biogas pipes and internal combustion engines.

Mukumba identified these factors in 2016, and one has to ask: Has anything changed since then? According to Yaseen Salie from the South African Biogas Association (SABIA) industry association, this still holds true. Salie believes biogas technologies should be implemented when a cross-sectoral need is met, such as when waste management/ valorisation and wastewater treatment are coupled with offsetting energy demands from the implementation site.

The attractiveness of biogas over conventional fuels and electricity generated from coal-fired thermal power stations is the possibility of a reduced carbon footprint and environmental and climate change impacts.

Mukumba also noted that community-based education on biogas products and their usage needs to be initiated to reduce biogas project failures. While Salie thinks community-based education on biogas products are essential within:

- Government – to assist in understanding what the enabling legislation and restrictive barriers are to biogas implementation

- Local communities – to highlight practical benefits in terms of energy accessibility, waste management and sanitation services.

- Biogas market stakeholders – to spotlight and share best practices in terms of project development and implementation.

The failures of biogas projects can often be blamed on poor:

- project development and management;

- communication and understanding between relevant stakeholders;

- knowledge of local context risks and complexities; and

- understanding of viable business case models.

Should the above problems be addressed and community-based education implemented, it could accelerate the growth of the biogas market.

GreenCape has developed a report on The business case for biogas from solid waste in the Western Cape, stemming from business interest and requests for information. Some of the general requirements for success were identified as the guarantee of consistent feedstock quality and quantity, reduced waste management costs and supplementing electrical and thermal energy used on site.

Besides, the economies of scale and the cost of managing are vital factors that influence viability. The study also found that small scale commercial biogas facilities (< 50kWe) are currently not financially viable for electricity generation. However, a medium biogas facility (50kWe–1MWe) utilising abattoir waste at the middle to high-end size range is economically feasible due to high waste management costs and energy demand on-site.

The Digital Global Biogas Cooperation (DiBiCoo) project aims to link European technology providers with emerging and developing markets for new investment opportunities and knowledge transfer. DiBiCoo is a cooperation project between biogas technology exporting and importing countries. The overall objective is to support European biogas and biomethane industries by preparing markets to export sustainable biogas/biomethane technologies from Europe to developing and emerging countries.

This project, it is hoped, will facilitate the introduction of biogas technologies and increase the share of renewable energy in final energy consumption, optimise project development and develop more informed policy, market support and financial frameworks.

As of Q1 2021, there is a renewed interest in the New Horizons Energy facility in Cape Town, with the IDC accepting an unsolicited bid. The initial launch of this facility in 2017 was not successful, mainly due to insufficient feedstock received. Still, it is hoped that more homogenous waste streams will be received as input material. There is a possibility that this plant may be operational again by 2022.

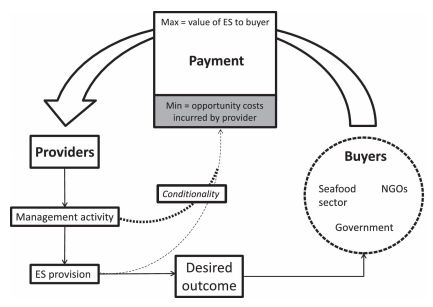

Figure 1: Demonstration of how a PES system would operate in the fishing sector. Source: GreenCape

With the looming landfill bans coming in place, there is an opportunity for this plant to receive high value, clean, homogenous streams of organic materials. Ideally, it would receive streams from industry generators directly, but there needs to be a logistical collection of separated organics from households, which could present another opportunity. This waste source will significantly improve the mixed municipal solid waste previously used as input feedstock.

SABIA is also in the process of introducing the Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) model as an improvement on the business case of biogas projects as it would provide an additional revenue model that can be included in the project. The proposed design of the PES (see Figure 1) model would focus on monetising the additional environmental value and benefits a biogas plant provides when implemented. For example, a farmer who may have previously disposed of his wastewater or manure into his lagoon would now be incentivised to treat those residues and reduce environmental impact. Similarly, an agri-processing facility sending its organic residues to landfill could be incentivised to divert and valorise those residues.

In terms of the South African landscape, there are 28 projects built and commissioned in the country, mainly commercial and industrial, according to GreenCape, although this is a nonexhaustive list. Plant sizes range from 12,5kW to 5,5MW equivalent, with most of the projects being below 1MW in size. SABIA reported in the launch of their market position paper that the average size of expected projects to be developed would be 250kWe–500kWe in size. During the same launch, SABIA highlighted a number of opportunities as seen in Graph 1.

In conclusion, the big question is whether there is a renewed hope for biogas in South Africa, with legislative changes being introduced. Salie is fairly optimistic. He is also of the opinion that should the norms and standards for organic waste treatment – currently being reviewed by the Department of Environment, Forestries and Fisheries – be gazetted, it will reduce the project development time in obtaining environmental approval and other permits.

In terms of using biogas for energy applications such as power and heat, the continuation of the Small Projects IPP Procurement Programme (SP-IPPPP); the development of a wheeling framework; and the small-scale embedded generation framework within municipalities will improve the business case for biogas projects. ESI